Visitors that stroll around the east side of the Estates will find the fall bloomer, goldenrod (Solidago). This simple, omnipresent “weed” became Thomas Edison’s obsession later in life, literally, until the day he died.

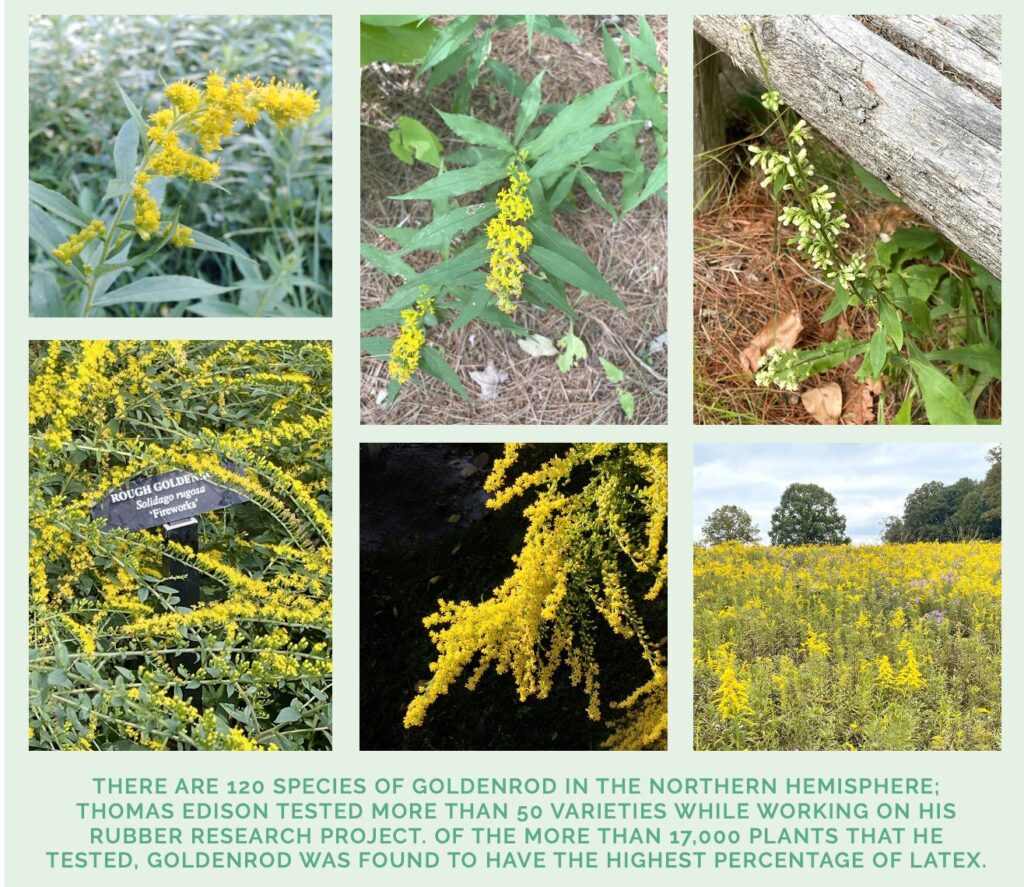

In the northern hemisphere, the arrival of autumn showcases 120 species of goldenrod, responsible for turning fields and hillsides into brilliantly sunny landscapes – and it is the adaptability, varieties and accessibility of the Solidago species that gave rise to some of Edison’s most devoted research. From the most common wreath goldenrod or blue-stemmed goldenrod (Solidago caesia) to the threatened Culter’s alpine goldenrod (Solidago leiocarpa), there is a goldenrod found in each state. The versatile goldenrod grows tall, short, multibranched, single-stemmed and is found in most habitats from xeric to hydric.

Edison and his compatriots, Harvey Firestone and Henry Ford, sought to ensure that America would not be dependent on rubber sourced overseas and goldenrod rose to the top of the list of 17,000 botanical candidates. In 1927, to the dismay of his wife Mina, Thomas had extensive rows of grapefruit and orange trees removed from the east side of the property (museum side) and replaced with goldenrod plants. The swift transition from an estate-like atmosphere to one full of disorderly looking grow beds, markers, and irrigation ditches did little to engage her enthusiasm for his renowned experiment.

The next year, the trio formed the Edison Botanic Research Corporation (EBRC) and built a lab on the Fort Myers estate. The new laboratory was designed by the Fort Myers architect Nat Gaillard Walker who also designed Edison’s riverside office, Mina’s teahouse, and the Moonlight Garden trellis enclosure. By 1929, Edison was growing orange trumpet vine (Pyrostegia venusta) a sun-loving, aggressive vine that grows to 30 feet tall, using sturdier goldenrod species as a support for the vines with the idea that they would be harvested together for rubber extraction.

Exhaustive research notes, most preserved in Edison’s own handwriting, detail his trials and tribulations with many species that were collected around the country and delivered to the Fort Myers laboratory and research beds. His team of collectors submitted several species for experiments trying to perfect Edison’s stated goal of a “good goldenrod,” which needed to yield 1,500 pounds of rubber per acre. One sample, found in Titusville, Fla., grew to 12 feet tall. As the fervor around his goldenrod experiment grew, 1929 saw Edison’s longest visit to Fort Myers – that year he stayed to work at the EBRC until mid-June. He further decided to halt the import of foreign goldenrod seeds, determining that the key to success was surely in one of the species found in the United States.

Testing more than 50 varieties of goldenrod, numerous ficus trees and a variety of euphorbias, the area beyond the banyan was described as a rubber plantation in the local press. Every state in the United States, has its own native species of Solidago, and some have several. The plant easily hybridizes, as Edison discovered. This herbaceous perennial is a keystone species – meaning it is among the first plants to reappear after a natural disaster. As it quickly revegetates disturbed areas, it also serves to stabilize soil with its robust root system to prevent further erosion following fire or flood.

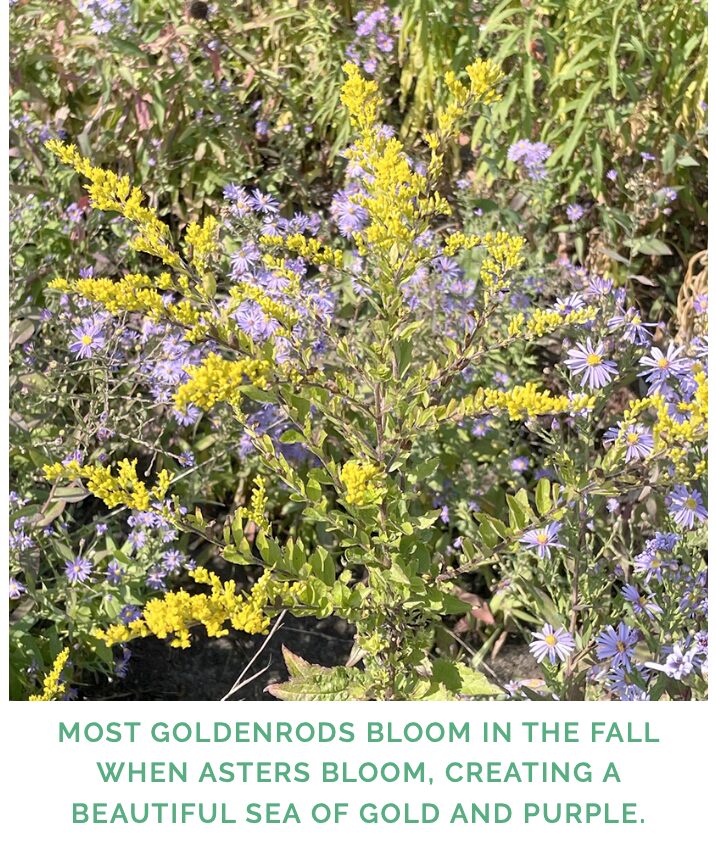

A member of the Asteraceae family, Solidago roughly translates to “make whole” due to its curative properties employed by early cultures. Typically, a late season bloomer, the plant is invaluable as a nectar source for a variety of butterflies, bees, wasps, and moths. The plumes make a great addition to any autumn floral arrangement either as a filler or for its cheerful yellow color.

Often blamed by hay fever sufferers for aggravating allergies, goldenrod is insect pollinated, where the real culprit, ragweed, is wind pollinated – right up into your nose! To distinguish, the leaves of ragweed are deeply lobed with an almost fernlike appearance, while goldenrod has lance shaped leaves known as entire, or smooth edge. Clearly visible on a sunflower (Helianthus), also a member of the Asteraceae family, those flowers are a composite head known as a capitulum.

Late in the summer of 1929, after Edison had returned to New Jersey from Fort Myers, a plant scout reported a goldenrod Solidago leavenworthii (Leavenworth’s Goldenrod) was found growing in 6 inches of water in a cypress swamp. Known as E.P.C. #573, 336 samples were removed from the discovery site and delivered to Edison’s Fort Myers experimental beds. The next month, another 6,000 samples were extracted and Edison asked they be delivered to New Jersey where he had taken ill. Soon, it was the only species of Solidago under cultivation for Edison’s experiment.

News of the “Solidago Solution” soon reached the press. Having to report back to the press that this experiment did not produce the desired results, Edison then became more reticent when probed about his rubber experiments. Unfortunately, the hurricane of 1929 destroyed many rubber research trees including ficus, eucalyptus and manihot and most of the labels of Edison’s test beds went with the hurricane winds. Following cleanup, a one-acre plot of the S. leavenworthii was replanted. Edison then offered a $25 bonus (approximately $500 today) to anyone who could find a goldenrod that would yield more than 5% rubber.

For the very reason that goldenrod is a keystone plant, re-establishing quickly after a natural disaster, two hybrids of the S. leavenworthii – namely altissima (the tallest species) and fistulosa (Pine Barren Goldenrod), multiplied from the original 100 plants to nearly 700!

In October of 1931, excited staff brought the first vulcanized rubber sample (when the raw rubber undergoes a chemical process that turns it into a durable product) up to Edison in New Jersey. He passed away several days later. It would be written that Mina believed her husband’s anxiety to find a viable rubber source contributed to his poor health.

Following the great inventor’s death, work continued at the EBRC. One hybrid that grew to a whopping 14 feet tall, was later named Solidago edisoniana, (syn. S. latissimifolia) or Giant Goldenrod and though it yielded 12% rubber, it lost too many leaves in the process. Earlier, Edison concluded that the weight of the leaves was a good indication of the plant’s potential rubber yield. In 1932, the sample identified as #EPC 573, the original S. leavenworthii, yielded 9.69% rubber content.

By 1933, two acres of goldenrod were planted in 13 plots, each 160 feet by 120 feet where the 6- to-8-foot plants created a sea of gold, though all that glitters is not gold. Solidago ‘bicolor/Silverod’ is a white goldenrod found exclusively in the Eastern U.S. Efforts for a natural rubber source in the U.S. became irrelevant with the invention of synthetic rubber in 1941.

The museum store at the Edison and Ford Winter Estates sells several books that cover this important research in much greater detail. It’s a fascinating journey for any botanical enthusiast.

For anyone wanting to learn more about gardening, several classes focusing on different topics are taught throughout the year at the Estates. See the website calendar for class dates and details at EdisonFord.org.